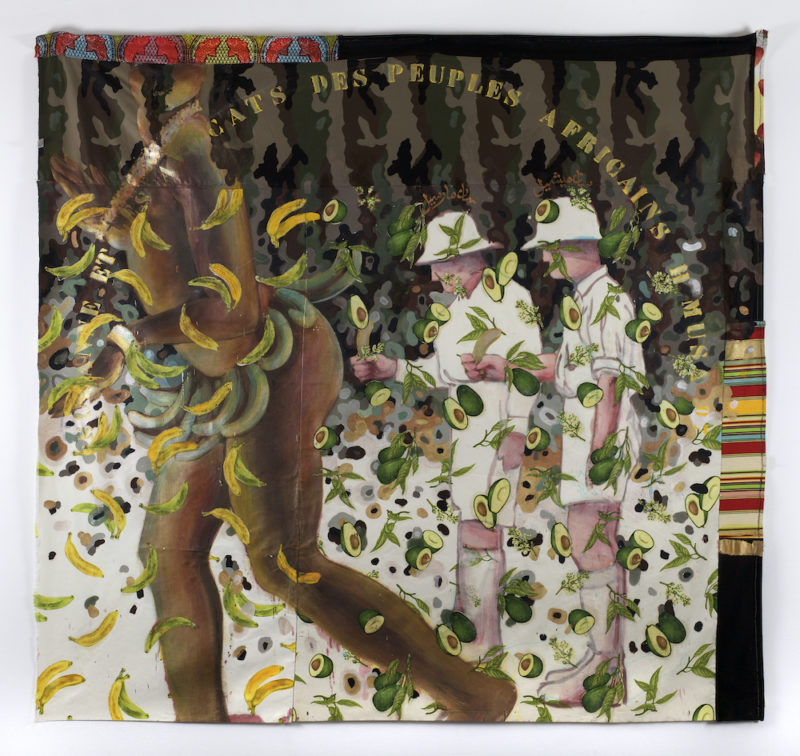

I see Josephine Baker as an american choreographer (translate : european choreographer), who managed to build a remarkable whole repertoire of primitivist choreography. Choreographies that she presented, on european stages, as “ african ” dance. But Josephine Baker was not only a choreographer, she was also a black american who found refuge in Europe after having experienced the misery and brutality of american racism at the beginning of the 20th century. However, when we examine the nature of the reception that europeans gave her, we see the same racist rejection, but expressed in a different way ; a subtle and biased racism that made her the representative of a both unbridled and diabolical primitivist sexuality, a black sexuality capable of satisfying all the erotic fantasies of the white male, christian and tamer of the wild world. In short, she was the ideal woman for Indiana Jones or for Michel Leiris, a young surrealist poet lost among ethnologists and promoter of ethno-aesthetics. If Josephine Baker became a chic sex-symbol of Africa in the Paris of the 1920s, it was not because she was the only “african” in this city. Paris has always known the black communities of Africa and the Caribbean. But Josephine was the black woman who was there, at the right time and in the right place, at the crossroads of the great socio-cultural contradictions of french society between the wars : colonialism, ethnology, fascism, surrealism, primitivism, art nègre, charleston and short dresses. She was the american tree that hid the african forest. Close to men of the calibre of Michel Leiris, Picasso, Van Dongen and Hemingway, she was in all the adventures of the parisian elite. In this respect, her participation and that of the black american boxer Al Brown, in the financial support of the ethnological mission Dakar-Djibouti seemed natural in the eyes of her contemporaries as a “ black woman ” helping “ her ” people with a black continent that she had however never known.

I do not see Joséphine Baker as the initiator of artafricanism but as a supporting base on which ideologues of ethno-aestheticism have inscribed their projects. For her part, Josephine Baker, happy with the manipulation of her image as a black woman by the negrophile elite of Paris – The Josephine Baker Story, Ean Wood, 2000 – evolved on the ruts of the path of european primitives. A path on which modern artists have left remarkable landmarks : Paul Gauguin, two decades earlier, had installed his Breton primitivism in a virgin tahitian forest reworked to the taste of parisians. As for Picasso, his contemporary, he combined pre-feudal spanish primitivism and art nègre under the admiring gaze of parisians (John Berger, The Success and Failure of Picasso, 1965). And in 1916, the dadaists organised at the Cabaret Voltaire, african evenings with the primitive masks of Marcel Janco (Ean Wood). I think that the cage in which Josephine sang and danced, disguised as a bird or a female savage, was not simply a music hall stage set. This cage represented, in the minds of the european public, a key metaphor for the culture of domination engendered by capitalist society in Europe. As a space of oppression and order where one can classify and contain the energies and beings of the “ messy ” world, the cage appeared as the appropriate place for africans. This symbolic tinkering of european racism was based on a whole tradition of “ indigenous village ” exhibitions, which, since the end of the 19th century, had represented the most constant element of universal exhibitions (John MacKenzie, chapter Les expositions impériales en Grande-Bretagne, in Zoos humains et exhibitions coloniales, La Découverte, 2002).

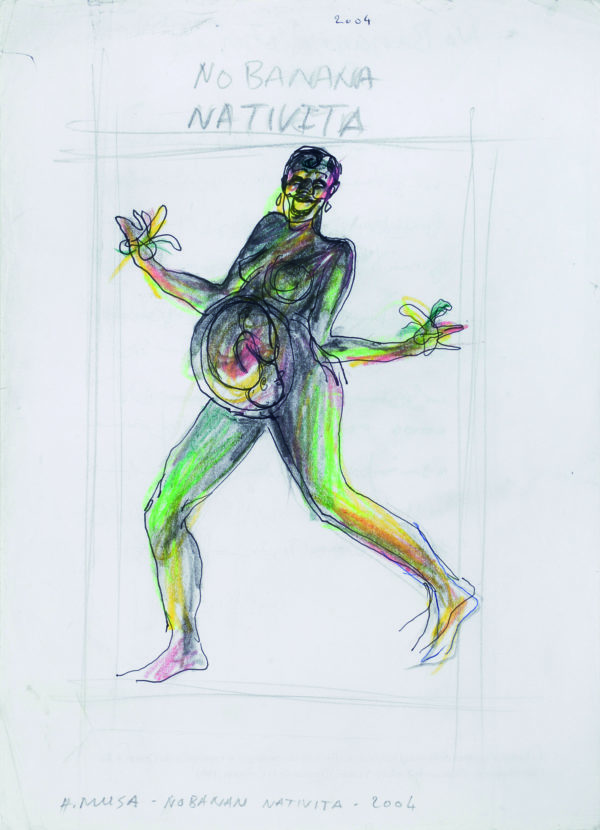

Exchange of emails between Hassan Musa and Kerstin Pinther for the catalog of the “ Black Paris ” exhibition (Bayreuth, Frankfurt and Brussels, 2006-2008). Pinther was one of the curators who designed the exhibition and the catalog of the exhibition “ Black Paris, Black Brussels ”.

December 15, 2006